Play to Cure: Crowdsourcing UK Cancer Research Through Gaming

2048? Angry Birds? Candy Crush? Whatever your game is, it can wait. Play a game that produces data for cancer research as you level up.

Crushing Candies or Curing Cancer?

The next time you start casually crushing candies or leveling up your warlock character during your morning commute, you might consider pressing pause and helping with some cancer research instead. Any of the games produced by Cancer Research UK’s (CRUK) Citizen Science projects can immerse you in the process of analyzing cancer datasets and providing critical inputs to professional cancer research.

Don’t you need to be a pathologist to do stuff like this?

As it turns out, not really. Cancer researchers have loads of cell samples that they visually / manually analyze – computers still aren’t good enough – and you don’t have to be a highly trained professional to understand and identify them. In fact, CRUK’s Citizen Science projects have developed games that enable people without scientific training to achieve greater than 90% accuracy in identifying cancer and non-cancer cells in tumor samples.

Alright, so what are these Citizen Science projects really about, and are they actually getting people engaged?

CRUK funds many of the scientists, doctors and nurses who lead cancer research efforts and have these massive collections of samples that would take close to forever for their small teams to manually analyze. With direct access to this treasure trove of data, and a noble cause to attract highly engaged, unpaid supporters, CRUK organized a 3-day hackathon in London, marketed as “Code to Cure,” that brought together 55 high-performing hackers who worked around the clock to prototype 12 games. Each game would engage average Joes and Josephines in the process of analyzing cell samples or other critical data to help CRUK-funded researchers accelerate or prioritize their testing.

Subsequently, CRUK worked with paid developers to fully build five games. Again, the social and emotional appeal of CRUK’s cause, as well as its access to real samples and data certainly helped get users engaged; however, much of the projects’ eventual success is also attributable to the fact that the organization ensured the games are seriously fun.

For example, some games are scientifically compelling, showing the most technically curious users exactly what a researcher would see. Others help accelerate cancer research one level at a time, providing gamers with a way to satisfy cravings to solve puzzles, go on adventures, and plasma blast asteroids.

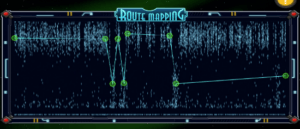

A microarray mapped via Genes in Space.

So what has come of all this?

Collectively, the games have won Digital Emmys, engaged more than 500,000 people across over 180 countries, and produced 11 million accurate analyses. These analyses have unlocked tremendous value for researchers and patients alike. For example, radiologist Dr. Anne Kilte of Oxford University relies heavily on heavily on citizen scientists’ contributions. Kilte and her team are searching for biomarkers in bladder cancer cells that indicate whether patients will respond better to radiotherapy or surgical removal of the bladder. Citizen scientists play games that help them identify and map the biomarkers in samples, allowing Kilte and her team to prioritize which sample’s they’ll use for further testing. Dr. Kilte says, “the beauty of Citizen Science is the sheer volume of analyses that are done. What normally takes three lab technicians a lot of time and work can be done quickly by the hundreds or thousands of people playing these games. In the end, we’re able to save time and money and give more patients greater confidence in their treatment decisions.”

What could the future hold?

There is no evidence that CRUK will directly monetize these games, but opportunities to do so abound, and the organization has only scratched the surface in terms of the potential for its crowdsourcing efforts. For example, growth opportunities exist across the other types of cancer for which CRUK funds research but hasn’t yet built games. Additionally, CRUK has opportunities to grow through partnerships with other games. For example, CRUK built an “exclusive level” for The Impossible Line (a four-star-rated mobile game), which required users to map their way through patterns of specks that reflected the density of matter in real breast cancer cells. Similar partnerships with other mobile apps could provide gamers a way to earn points for use in the core game itself, give cancer researchers access to additional data, and present plausible opportunities for CRUK to raise funds. For example, one might imagine CRUK making these exclusive levels available through in-app purchase and arranging revenue-sharing agreements with app development companies. Finally, CRUK could provide its Citizen Science gaming services to other researchers and foundations. In the interest of the entire research community, CRUK may not want to monetize this as a service, but bringing other researchers’ data onto its platform could provide rapid growth in the total volume of completed analyses and give CRUK’s researchers opportunities to really accelerate research and collaboration.

Game over

So, the next time your Mario loses his last life to a Goomba attack, consider saving another life and leveling up your own by joining the effort to accelerate cancer research. Go ahead and choose from one of the games below.

_____________________________________

Play to Cure: Genes in Space

The mission of the free mobile game “Play to Cure:Genes in Space” is to collect a fictional substance dubbed Element Alpha, which represents genetic cancer data that might underpin certain types of cancer. Thanks to Genes in Space, over 400,000 people were able to collectively analyse four kilometres of breast cancer DNA in two years.

Reverse the Odds

Help a band of colourful creatures whose world is falling into decline, by completing mini puzzle games and rebuilding their magical world. Earn points by answering simple questions about lung and bladder cancer samples.

Reverse The Odds had over 135,000 downloads world-wide and more than 4,500,000 contributions. The game won, among other awards, a Digital Emmy and received high praise from the gaming industry and scientists alike.

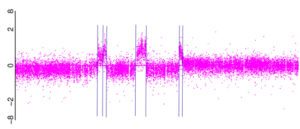

The Impossible Line

Spot genetic faults in breast cancer data. In the lab, scientists map these faults to better understand how mutations cause different subtypes of breast cancer. In CRUK’s exclusive level, players map these faults by navigating through patterns of specks.

Cell Slider

A web-based app showing samples of breast cancer tumors. The images themselves usually contain a mixture of different looking cells. Some might be cancer cells; others healthy breast cells, and some might be the supporting tissue surrounding these cells. The challenge for the Citizen Scientists is to spot the cancer cells following a short tutorial when they sign up. The images are also colored based on how much of a particular molecule, called oestrogen receptors, the cells produce.

Over 2,000,000 contributions to date.

Trailblazer

Players see images of tissue cores and mark areas of cancerous cells after going through a tutorial.

Adam, this is completely fascinating! This reminds me so much of Captcha and Duolingo, which both involve crowds doing one action – which actually serves a completely different purpose. I think it is fascinating to see cancer research gamified in this way. I can see many people (myself included) downloading all of these games as a way of having a small amount of social impact while relaxing.

How have they gone about attracting users to download these apps? It seems that users would be intrinsically motivated to play them (out of a desire to help cancer research while playing) – but that many people probably still don’t know that these exist.

Also – I wonder if these need to be monetized on the user side at all. Perhaps their development could be covered in part by cancer research budgets?

This is really amazing and I greatly appreciated learning about this! People always talk about ‘gamifying’ online ads but I had never thought about how a game could be used to interpret a dataset. Beyond assisting with scientific research, I wonder what other potential game design could be used to better understand underlying data in any industry? What insights might be able to be extracted by encouraging people to play games that produce a certain utility for a 3rd party, which is no doubt very compelling in your analysis.

This is really amazing and incredibly creative way to involve and engage the crowd, getting them to do work for you without even knowing it. I agree with Sonali that the missing piece here is the marketing element to attract user growth. There is obviously tremendous benefit to attracting more users and given it’s mission. The monetization question is challenging as it certainly feels wrong to charge their gamer-users to help them process cancer research, but I could see benefit in funneling the profits back into expanding the user base and/or going towards funding more cancer research. I wonder how public they are about telling their gamer-users that they are actually processing and helping with cancer research data while playing these games.