DeNA Case: Failure of HBS Alumna

Risk of crowd sourced information

Overview of the case

On December 7th, 2016, Ms. Tomoko Nanba, Founder, Representative Director and Chairman of the Board of DeNA, made a press conference to apologize the scandal about its medical information business for its systematic engagement in providing unreliable crowd sourced information and plagiarism.

HBS alumna as the Japanese rising star

Ms. Tomoko Nanba, a former McKinsey consultant and HBS alumna (Class of 1990), has founded DeNA in 1999. The early history of DeNA was a provider of online auction platform. The company listed on Tokyo Mothers (equivalent to NASDAQ of USA) in February 2005 and on Tokyo Stock Exchange in 2007. She took many important social roles such as the member of IT Strategic Office of Japan Cabinet and the member of the Council for Regulatory Reform of Japan Cabinet. She was seen as the role model of female entrepreneur and her business flourished and expanded from e-commerce to game apps development and professional baseball team management, including curation media business which caused the scandal.

DeNA business line

Source: DeNA website

The scandal

The problem surfaced in October 2016 when people found out that the advertisement article of WELQ, the medical curation media platform of DeNA, comes up in the top ranking of the search result when they put certain keywords such as “want to die”. It faced the public scrutiny and the major online media Buzzfeed published a whistle-blowing document containing insider manual of WELQ. The document revealed the systematic engagement for the malpractice of the company. The major problems of their engagement were the use of crowd sourced articles from non-experts and plagiarism.

First, WELQ solicited articles with explicitly stating “anyone can write” and offered only Yen 300 to Yen 500 (USD3 to 5 equivalent) for a 500 to 1,000 word article. Buzzfeed and media criticized that the price was too cheap and accused the company that they implicitly encouraged plagiarism from other sources as the price did not make sense to write an article from scratch. As the result of the guideline, WELQ obtained and provided more than 100 new articles per day, leading increase of viewers and, ultimately, advertisement clients. As a result of the practice, it obtained more than 6mn users per month when the problem was revealed. However, there were also so many articles and information which were not factual or accurate.

Second, more explicitly, the insider manual clearly stated that writers should utilize other media resources as references. Moreover, the manual recommended writers to change the wording of the sentences of which they used as references. These guidelines were the clear evidences of the organizational involvement in the plagiarism and the infringement of copyright.

Needless to say, not only WELQ provided the insider manual and encouraged the aforementioned malpractice but also it clearly lacked the screening system to guarantee the accuracy of the information. Because WELQ was the medical information platform, the accuracy of the information was the most crucial factor to obtain customer loyalty and brand equity. The scandal completely shattered both.

Outcome

This was the first case that the accountability of the curated information was focused in Japan. Amplified by DeNA’s social status as the founder was one of only few succeeded female entrepreneurs and highly regarded in Japanese society, the public criticism was really harsh.

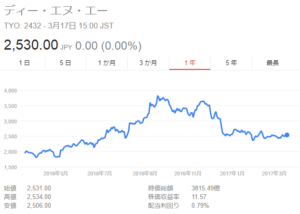

Even though the financial impact of the scandal to DeNA was only Yen3.8bn (USD40mn equivalent) impairment loss due to closing its 10 online curation sites, the impact of the loss of trust was tremendous. The stock of DeNA plummeted 42% (from Yen3,820 to Yen2,364) and it lost Yen220bn value (USD2.4bn equivalent).

Stock trend of DeNA

Source: Yahoo Finance

Takeaways / mitigations

The case taught us that the company should be responsible to what it provides to users, especially if the potential impact of the products / services/ information could be huge. In DeNA’s case, it could have reduced the level of social infuriation if the curation media did not focus on medical and healthcare. Of course, the best course of action is to be accountable of the information it provides and set the stringent screening process to conduct reference check of writers and articles, in order to guarantee the accuracy and legitimacy of the information.

Reference

- https://dena.com/intl/company/overview/

- https://dena.com/intl/

- http://dena.com/intl/press/2016/12/statement-regarding-denas-curation-platform-business-by-isao-moriyasu-president-and-ceo.html

- http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/12/02/business/corporate-business/dena-pulls-eight-online-services-amid-reporting-scandal/#.WNAanG81_IU

- http://www.j-cast.com/2017/02/09290182.html

- https://www.buzzfeed.com/keigoisashi/welq-03

Thanks for the post, Tomo! Sometimes the pressure to be the biggest platform the quickest can really take its toll. It’s also interesting that you can run a good crowd-sourced reference website if you pay people nothing (e.g., Wikipedia) but adding a small financial incentive may do more harm than good.

Thanks for the comment Meili!! I cannot agree more. I think it really depends on the customer expectation. If users know the service is free of charge and understand the disclaimer that the service does not guarantee the accuracy of the contents, users should be more receptive. In DeNA’s case, even though the company did not get fee from users, users knew that the company got revenue from advertisement and the users felt they were exploited. I have no doubt that this was one of the causes of the social resentment.

Fascinating post Tomo – how disappointing to see an HBS alumna promote such unethical actions in the name of growing a business and profits.

I agree with Meili’s comment – I found myself thinking about Wikipedia as I read your post. Wikipedia has developed a set of devout writers who, despite not being paid, are loyal to constantly writing and updating the site. I wonder if there would have been a way for DeNa to have developed that level of loyalty to the platform through ranking the writers and labeling them as “experts” as their work was reviewed and approved. Of course this requires a level of accountability to the writing on the site (as you have alluded to in your takeaways).

Additionally – I have heard a number of doctors and friends speak against “Web MD” and self diagnosing. As someone who has definitely googled symptoms of such ailments as sinus infections etc, I know how valuable it can be to have a quick check on whether I should be concerned about an illness. However I completely agree with your comments above – there needs to be a sense of accountability and responsibility to the content that is published on the website. Thank you for sharing an example of a time where that responsibility just wasn’t in check – I think it demonstrates how serious each of us needs to take accountability for our future businesses to ensure whatever product/service/resource we provide the world does good rather than potential harm.

Sorry for my late response Megan. Rating system is great and that is something I haven’t thought about. It can not only increase the accountability but if we can encourage readers to rate the article it can reduce the labor cost for the company and it can serve as a third party audit function.

DeNA neglected the accountability issue due to its small size of the business but this case taught me the small side-business can endanger the whole organization if it ruins reputation and brand equity.

Great case Tomo!

Though this is a negative story, I do see the Japanese society taking good quality information seriously.

The issue of DeNA has been perpetuated by Baidu’s “Zhidao” platform at a much greater extent, where writers are paid virtual currencies. As a result, there was a lot more low-quality content on Baidu Zhidao such that readers do not trust them any more. Now the more trustworthy site is Zhihu, which is similar to Quora. The profile of the writer is attached to the article, providing authenticity and credibility.

Tomo, thanks for sharing this case study about the failure of crowd-sourced information platform. I would love to know how you think this could have been prevented? In such cases, I always refer back to Wikipedia (as Meili and Megan mentioned too). While it is not paying their editors any money to contribute to the content, it has put in place a hierarchical editorial team to enhance consistency and sanctity of information. That being sad, you still can’t always trust all the information on Wikipedia. Wikipedia does, however, provide references to the information in the articles. (shameless plug: see my blog on Wikipedia: https://d3.harvard.edu/platform-digit/submission/wikipedia-the-free-encyclopedia/). Similarly, Quora is also free crowdsourced content where contributors are not getting any monetary benefits.

In light of these, how do you think DeNA type instances can be avoided by similar platforms?

Sorry for my late response Mohit and thank you very much for your comment. I cannot agree more with you that one of the major differences between DeNA and Wikipedia is the existence of editors. I believe if they have internal or external editors who oversee the accountability of articles, as well as the inclusion of references, they could have mitigated this issue.

Also, I believe if DeNA have had more customer oriented mission, they could have avoided this issue. They did not focus on customer satisfaction at all but merely viewed customers as a source of revenue (to funnel advertisers into the platform). If they had the customer focus culture or mission, they would not have employed such a untrustworthy initiatives.